By: Simon Brooke :: 2 October 2024

On the corruption of justice

The nature of justice is that it should be just. That it should be fair. That it should be equal. Without, in the clichéd phrase, fear or favour. The duty, then, of a public servant appointed to administer justice, is to administer it fairly; and if that person fails to do so, they are failing in their duty, and should be, at the very least, reprimanded, and if their behaviour does not change, dismissed.

Further: if a public servant appointed to administer justice accepts a specific gift, as US Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has notoriously done, from someone who may wish to influence a decision of his court, than that's very clearly a malfeasance: in terms of English or Scots law, misconduct in public office. It's clearly corrupt. But is the acceptance of a specific, identifiable gift from a person with an interest in influencing a decision of the court, a necessary condition for a judgement of corruption, or it merely a sufficient condition? Would, for example, a judge showing a pattern of substantially more leniency to defendants who might be expected to be in a position to make substantial gifts in itself be evidence of misconduct in public office?

What?

I'm responding immediately to an essay by George Monbiot in yesterday's Grauniad; but George's essay wasn't telling me something I didn't already know, probably wasn't telling many alert people in the UK something they didn't already know:

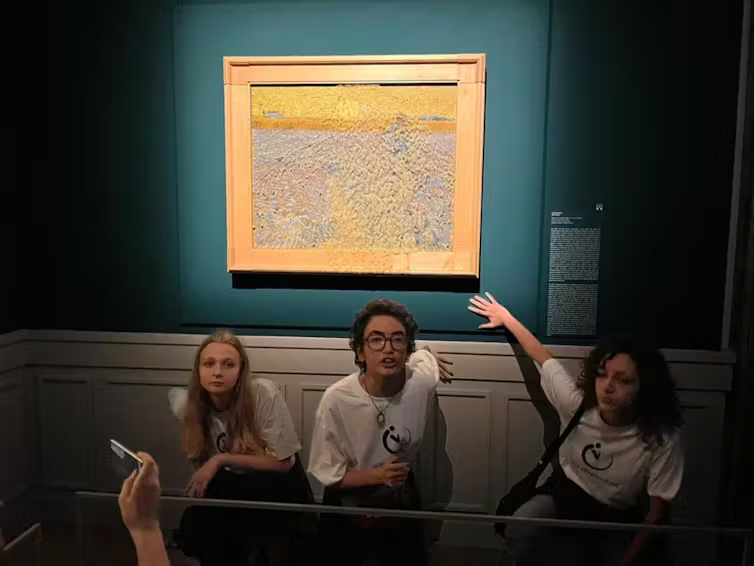

...in the placid setting of Southwark crown court two young women from Just Stop Oil, Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland, were sentenced to two years and 20 months, respectively, for throwing tomato soup at the glass protecting Van Gogh’s Sunflowers...

The argument that Monbiot is making is that Hehir penalises non-violent climate protesters much more severely than people accused of acts of malicious violence, and I think it's a case he makes successfully. Full disclosure, one of the people likely to come before Hehir's court on a charge of non violent protest is an extremely close friend of mine — who I personally regard as a hero. But in this, Hehir is serving, if not the public, at least the state: successive UK governments, both Labour and Conservative, have imposed increasingly repressive penalties on non violent political protest, and in administering these penalties Hehir is acting as a good servant of that state.

On legitimate and illegitimate law

Note that this does not, in my opinion, absolve him of misconduct in public office: as a justice, his duty is to administer justice on behalf of the public, not of the state, and where the law is unjust, a justice must refuse to execute it.

Besides that, there is the question of how it comes to be law that non violent political protest is penalised so heavily. As I've observed elsewhere, law is a mixture of two things: rules made by the privileged to protect their privilege; and a lagging indicator of social consensus. I would further argue that laws of the second type are legitimate: that they ought to be obeyed, even if one personally disagrees with them; but that laws of the first type are illegitimate, and should be openly flouted.

So, is there a social consensus that non violent protest should be heavily penalised?

There is not.

Polling commissioned by the University of Bristol indicates that only 29% of people in the UK believe that non violent protesters should ever be incarcerated. An equal number believe that non violent protesters should not even be fined. Almost half (13%) of the group who believe that non violent protesters should be incarcerated stipulate that sentences should not exceed six months.

So, if two thirds of the UK population believe that non violent protesters should never be incarcerated, and five sixths of us believe that non violent protesters should not be incarcerated for sentences in excess of six months, why are two young women being sentenced to periods of incarceration exceeding eighteen months each for smearing a piece of armoured glass with Heinz Tomato Soup?

Because, let's face it, the accused knew, and Judge Hehir certainly knew (because he mentioned it in his judgement) that the glass was there. The soup was thrown 'at' the painting in exactly the same sense that a rotten egg is thrown 'at' a celebrity in an armoured limousine. The direction of travel may be correct, but the intervening barrier, by design, prevents the projectile reaching the target. The action was pure theatre. The only thing that was ever at risk was a sheet of a common, inexpensive, mass produced industrial product — an item that was there precisely because it was utterly impervious to foreseeable threats — and everyone concerned in this case knew this to be true.

What's also true, of course, is that tomato soup washes off armoured glass extremely easily, as anyone who has a pyrex dish in their kitchen knows. Cleaning the frame surrounding the pane of glass, and the wall below the pane of glass, may be a little more difficult and take a little more time — but no-one is pretending that either the frame or the paint on the wall are in any sense irreplaceable.

So this was a massive — a crushing — response to an almost trivial offence. Why? Why is a democratic state so fearful of dissent that smearing a pane of glass with soup must be punished with years of jail time? Why, when the electorate are generally fairly tolerant of non violent protest, do elected governments ramp up the penalties to these ludicrous levels?

Well, again, as I've observed before,

It's one of the features of modern Western democracies that political parties seek their crucial election finance from those people who have surplus wealth, and those who have surplus wealth are by definition those who are profiting from the status quo.

Our 'democratic' political parties are elected by the people, true; but they pay surprisingly little attention to the views of those who elect them. They receive their funding from the ultra rich, and from large corporations; and it is these paymasters whose tunes they play. The Grauniad has documented how — unsurprisingly — the oil and gas industry has drafted, promoted, and vociferously lobbied for anti-protest laws in the United States. While observing the same process happening internationally, the dear old Graun is more circumspect about pointing specific fingers — no doubt in (reasonable) fear of litigation from dark money. But it stretches credulity that it is not the same malefactors at work.

As I wrote above:

Further: if a public servant... accepts a specific gift... from someone who may wish to influence a decision... than that's very clearly a malfeasance: in terms of English or Scots law, misconduct in public office. It's clearly corrupt.

The question applies equally to those who serve the public in the executive or in the legislature as in the judiciary.

However, that's not my argument here.

Apparent discrimination in favour of the ultra-rich

My argument starts from what is virtually an aside in Monbiot's piece:

The same judge, Christopher Hehir, presided over the trial of the two sons of one of the richest men in Britain, George and Costas Panayiotou. On a night out, they viciously beat up two off-duty police officers, apparently for the hell of it. One of the officers required major surgery, including the insertion of titanium plates in his cheek and eye socket. One of the brothers, Costas, already had three similar assault convictions.

Let's start this section with a very clear and simple observation. If a judge should, systematically, pass harsher sentences for black offenders than for white offenders in similar cases, that would be a serious malfeasance. To prevent such issues arising, justices in England and Wales have an Equal Treatment Bench Book outlining the standards they are expected to adhere to. This 'bench book' does not, of course, cover only racial discrimination. Chapter eleven of the current edition of the bench book is specifically concerned with 'social exclusion and poverty'. Of course, the current edition did not exist in 2014, when Hehir sentenced the Panayiotou brothers. I don't have access to the guidance that was in place at that time.

However.

However, I've been reading through the summaries of cases heard by Hehir on The Law Pages. He's jailed a lot of people for non violent political activism, true; but he jails a lot of people. I do not suggest that he has a particular animus towards non violent protesters. He is a custodial judge in the same sense as Judge Jeffries was a hanging judge. Overwhelmingly his most common sentence, over a wide range of offences, is 'custodial intermediate'. And, indeed, in what appears to be the specific case of the Panayiotou brothers, he said, before sentencing, "it seems to me that the custody threshold is clearly passed in this case."

Clearly.

It's hard to disagree with him on this; there are a series of aggravating factors in this case:

- The person most seriously injured was a police officer, albeit off duty;

- Passers by were also violently attacked;

- The attacks were unprovoked;

- At least one of the officers was attacked from behind;

- Allegedly, one of the brothers, Costas, already had three previous convictions for assault.

There was also, however, one significant mitigating factor:

- The brothers were heir to a reportedly £400 million fortune.

That sort of money can, as I've observed before, buy a lot of impunity.

And so, as Monbiot reports, when the time came actually to pass sentence, Hehir had had a miraculous conversion. I have searched. I have found no other cases where Hehir has ordered a non custodial sentence in a case of unprovoked violent assault. Perhaps there are some.

It was on — or at any rate by — the 3rd April 2014 that Hehir observed that 'the custody threshold is clearly passed'; it was on the 2nd May of that year that a custodial sentence was not handed down. So what discussions, what meetings, what quiet words in ears, had influenced him in the interim? We don't — publicly — know. Whether there has been any investigation into the matter we also don't — publicly — know. And I feel that in that lack of public knowledge, that lack of transparency, there is a severe problem — a severe taint.

For a public servant to appear to be more lenient to those who are very rich than to those whose cases are otherwise similar but are not, smells very rank. A judge, like Caesar's wife, must be above suspicion.

P.S. Those absolute heroes, Led By Donkeys, have just published a video about the same issue.

« Recumbent drive trains | | Resignation of Rosie Duffield MP »