By: Simon Brooke :: 19 February 2025

Dumfries and Galloway Council, acting on direction from the Scottish Government, wants each community in the region to produce a document called a 'Local Place Plan' summarising its planning issues and priorities. Auchencairn has made no progress on this over at least two years. As incoming chair of the Community Council, I've set up a working group with representatives from other key civic society groups within the village, and started working on the plan. Because the deadline is now tight, we've had to work fast.

As part of this process, I've led the working group in preparing a questionnaire for villagers which explores questions which may be in contention within the village. This isn't 'my' questionnaire, it is a group effort; but it's fair to say I've led the effort.

Among the documents that the Scottish Government prepared for communities preparing Local Place Plans is a thing called the 'Place Standard Tool,' which is, in fact, a questionnaire. It's fair to say that I hadn't adequately studied the Place Standard Tool before starting work on our own questionnaire.

Voices within the village are saying we should abandon our questionnaire, and only use the Place Standard Tool. My very strong feeling is that we should not, that we should instead use both; but I'm writing this essay this to try to evaluate how rational that feeling is.

As — by a very long way — the most left wing person on the Community Council, I cannot win every decision. I have to build alliances, and I cannot afford to burn goodwill on fighting fights that don't really matter.

So: does this matter?

Is the Place Standard Tool different from our questionnaire?

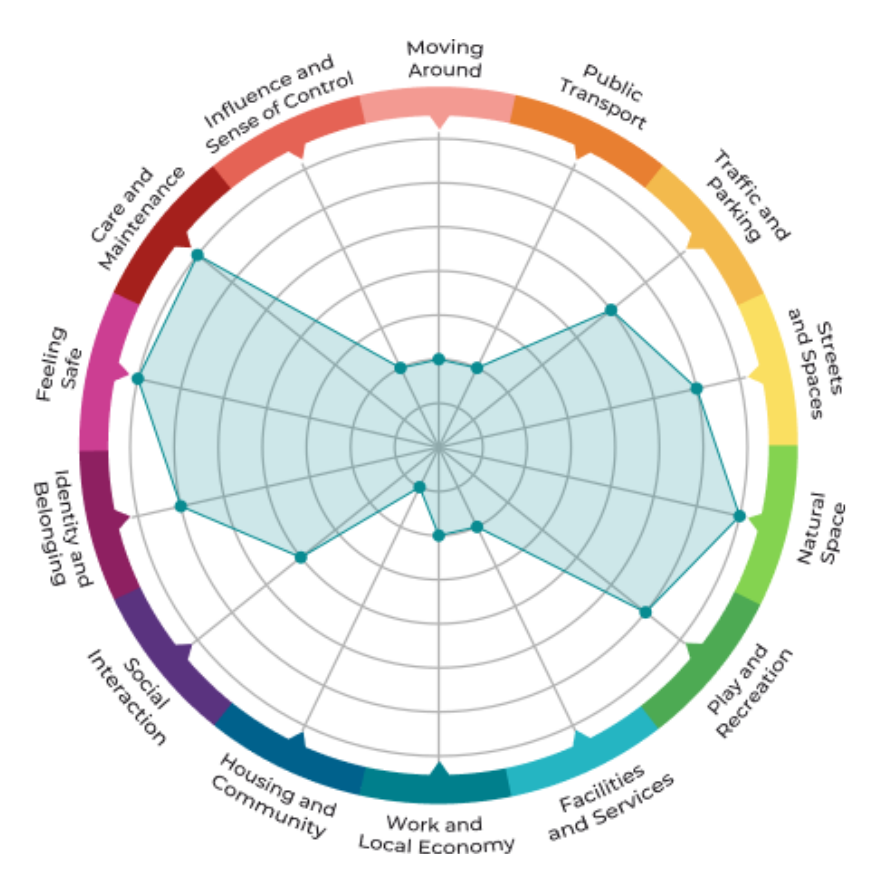

Yes, it is. The Place Standard Tool asks fourteen very broad questions, each of which is scaled along an eight point scale. It allows extensive narrative supplemental answers to each question, divided into two sections: 'What is good now?' and 'How could we make it better in the future?'

The Place Standard Tool is designed to be administered across all the communities of Scotland, the vast majority of which are not remote rural villages. Therefore it has to be broad. It's also, probably deliberately, fairly bland. It does not ask about things which are likely to be contentious. You can obviously talk about contentious things in your narrative answers, but the nature of narrative answers to large questionnaires is that they're extremely hard to summarise, or to draw conclusions from.

In being so general and so bland, it unfortunately conflates two very different things: it generalises 'Housing' and 'Community' into one question, measured on one eight point scale. Housing, in Auchencairn, is in utter crisis: we have homelessness far above the national average. Community is Auchencairn's great strength. To try to measure both along a single axis will produce no signal, but only noise.

By contrast, our questionnaire asks focused questions about things specifically relevant to Auchencairn. It asks about whether we want to keep the school and nursery open. It asks about what measures we're prepared to take to make sure that people of child rearing age are able to afford to live in the village. It asks about our attitude to people living in informal accommodation. It asks where we're prepared to have electric car charging points put. It asks about what we think farmers should be allowed to do with the land.

These questions are contentious. They're deliberately contentious, because unless we know where a majority in the village stands on each of those issues, the Community Council cannot make decisions on those issues which serve the community.

Contentious questions make people uneasy, and it's easy to see why they do. They expose the fault lines that we all know run through the village. But they provide information which I believe to be essential to planning the future for the village — a future which the village community, or at least a significant majority of it, can be united behind.

Of course, it's possible that that plan which a significant majority can be united behind would exclude me; I am to an extent an outlier, both literally and metaphorically.

The background

The only house in this village registered with the Solicitors' Property Centre today as being for sale is seeking 'offers over £525,000.' That's half a million quid — or more. That's a relatively big house, and a relatively high quality one; but few houses in the village go for less than £200,000.

15.6% of all full time employees in Dumfries and Galloway generally, and, probably, more in the rural Stewartry, earn less than the living wage. The median annual income for full time employees in the region is £31,106 (£598.20 weekly) — said to be 'the lowest gross median weekly pay for full-time employees of [all] 32 Scottish local authority areas in 2023'; and again, one can reasonably expect that in the rural Stewartry, it's lower. The largest repayment mortgage one can take on on an income of £31,106 is about £125,000.

Which is a way of saying, people who earn their living in Auchencairn, unless they have substantial inherited wealth, cannot afford to own a house in Auchencairn. Their opportunities for renting are also limited, because there are few private rental properties and also few social rent properties. Furthermore, private rents are very variable; the profitability of holiday lets tends to drive prices of residential rents up.

In consequence, there is now, as far as I'm aware, only one house on Main Street occupied by people whose parents lived in the village (the former Methodist chapel, which is occupied by a second generation villager, is on the corner of the Square; I don't think it counts as Main Street but if it does, that's two). The vast majority of those second generation villagers who still live in the village itself at all now live in social housing, creating a situation where it's possible to say with a perfectly straight face that the native people have been ethnically cleansed into a reservation — a Bantustan — on the other side of the burn.

That is, of course, an extremely provocative thing to say, but it is also literally true. This isn't to say that individual incomers are bad people. They're not. It's reasonable for elderly people with a substantial reserve of capital to want to spend their retirement in a beautiful place. And all the (native) people who sold their houses at inflated prices to those wealthy incomers did so voluntarily. It's a consequence of capitalism that those with money will move into places which are beautiful but relatively impoverished, and, by doing so, drive out those with less money. It's not a fault of the people: it's a fault of the system.

There are, to my certain knowledge, at this moment at least 29 people in Auchencairn Community Council area living in 'informal accommodation', which is to say in old vans, caravans, tents or huts. Some, not all, of those people are people who have lived here a long time. Some, not all, of those people are second generation villagers. People say, "oh, that's a lifestyle choice;" and that, too, is an extremely provocative thing to say — one which makes me, personally, extremely hurt and angry. Living in cold, meagre, insecure housing partly is a lifestyle choice, true; but it's a lifestyle choice conditioned by the unaffordability of housing in the area.

As Anatole France wrote, "the law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal loaves of bread."

Why do I care?

Well, first of all, I care because I'm one of the people who live in a hut; and although I wouldn't move from my hut to any other accommodation which I could possibly afford, my hut is not a very satisfactory home in which to grow old, and I do genuinely wish I could afford to build something better.

But second, I am a person of place. This village is my place. I first came to it in about 1966; I returned to it as an adult in 1977, to set up my first business. That business, and with it my first marriage, was destroyed by Thatcher's first recession, and I went away to university. But in 1998 I came back, because my home was here; and I've lived here ever since. My mother and my sister are buried in the village graveyard; half of my niece's ashes are there, too.

This is my place: I have a very strong commitment to it.

Why do I have such a strong commitment to it?

I think because it was the place where, as I first spiralled down into acute madness as a child, I was safe. The only place I felt safe. The place where I could walk the hills and the woods, ride around in the back of the shepherd's pickup tending new born lambs, help clean out the byre after milking, drive a tractor at hay time to haul bales back to the barn, sail my little boat, explore the geology and the biology of the landscape — all without continuously facing demands and expectations I could not meet.

It's also the place where I spent the happy years of that first marriage; where I bought, and restored, and sailed the most beautiful boat I've ever owned. And it's a place where, for all my faults, I've been accepted, and even welcomed.

When I collapsed into insanity again in 2009, and lost my beautiful home in the centre of the village, I could still have afforded to buy a small house in the east Ayrshire coal field or a flat in East Kilbride or Cumbernauld. I didn't do that. I thought, reasonably I think, that if I did that I would be on a certain road to suicide within the year. Instead, I bought a field and a little wood, and built my little illegal hut, hidden among the trees where it couldn't be seen.

That was (obviously) a mad decision. I make no excuses. I was clinically insane at the time. As evidence that it was in fact a good decision, I'd point to the fact that I'm still alive, and still having at least some positive influence on at least some people's lives.

Why this matters

[Retirees] arrive at about sixty-five; for ten years they energetically involve themselves in local activities, and during that period learn something about the locality. They buy their groceries locally, service their car locally, get their hair cut locally, use health-care services locally. For ten years, they contribute. Then, at around seventy-five they become infirm... At around eighty-five they die, and are replaced by a fresh wave of energetic sixty-five year olds arriving from the cities...

You cannot build or maintain a community on the basis of a rolling population of elderly strangers, no matter how talented, well meaning and energetic.

Again: this is not an argument that the incomers are bad people, either individually or as a group. Like any other mass movement of people, the individuals are driven by perfectly reasonable, perfectly rational choices. Like any other mass movement of people, it creates problems for the receiving community — which a good community will cope with.

It is my aspiration that Auchencairn should be a good community, that it should find ways to welcome and to integrate all of those who want to come here and contribute, whether rich or poor.

But realistically, Auchencairn faces two possible futures: it can become an enclave for rich strangers to live out their last years in a chocolate box simulacrum of village life; or it can remain a multi-generational community with infants, toddlers, children, adolescents, students, courting couples, harassed parents, confident adults, wise elders.

Both of these futures are possible; but the first is much more likely than the second. Unless we make significant planning interventions, the first is the inevitable consequence to which the the invisible — and blind — hand of the market will drive us. Are we, as a village, comfortable with that?

We cannot know.

Unless we ask ourselves.

Tags: Auchencairn, Levelling, Galloway, Living Spaces, Rural Policy